A quantitative analysis of records on silver, copper, iron and lead/zinc mines in the Ming and Qing Veritable Records (Shilu 實錄)

The purpose of this survey

The Veritable Records are the day-by-day synopsis of all matters brought before the emperor that survived for the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. Each entry on a matter is the summary of a concrete matter that either required an imperial decision or was considered important enough to be brought the emperor's attention. Diligent emperors listened to several dozen to hundreds of matters every day. This vast source covers an enormous breadth of issues and allows assessing their importance to the central government. Since the Veritable Records have been made readily accessible by digitization, they are a popular source studying how the central government worked, which topics were important, and what was known at court. This survey uses the source for government attitudes towards metal mining.

The keyword search

The survey is not an exhaustive search for all entries concerned with metal mining in the Veritable Records of the Ming and Qing dynasties but a selective search in the full-text database for the binoms that directly refer to silver mines (yinchang 銀場 or 銀厰), copper mines (tongchang 銅場 or 銅厰), iron mines (tiechang 鐵場 or 鐵厰) and lead or zinc mines (qianchang 鉛場 or 鉛厰). The search yields between a quarter and a third of all entries concerned with metal mines.

Due to the search for binoms, records that contain the place name but omit the exploited metal or mention the metal in other contexts are not covered. Moreover, also occurring references to “miners” (kenghu 坑戶, kengmin 坑民, changmin 厰民, kuangmin 礦民, kuangtu 礦徒), smelterers (yehu 冶后 or luhu 爐戶), “ore/mining site” (kuang 礦) “smelter/smelting site” (ye 冶) “furnaces/smelters” (lu 爐) pits (keng 坑) or workings (dong 硐) and related terms have not been included.

The metals covered in the search are silver, copper, iron, lead and tin. Qian 鉛, originally referring to lead came to be used for zinc as well, when metal zinc was discovered. The term woqian 倭鉛 is the specific name of zinc found from the mid-Ming, while Qing sources usually differentiate “black” and “white” lead (heiqian 黑鉛, baiqian 白鉛) for lead and zinc. As both qian and its binoms are used in the texts and as many sites exploited both metals, the differentiation between the two metals is often difficult. In the presentation of results, the two metals are grouped together. Other metals, which by the definition of the period would be included in metal mining, were tin (xi 錫), mercury (shuiyin 水銀) and cupro-nickel (baitong 白銅). Because mines exploiting these metals were relatively few, I have not included them.

The purpose of the survey in not an exhaustive search for all entries on the topic but a quick and representative impression of overall frequency and the distribution of metals as well as the geographic distribution of the matters brought before the emperor in late imperial China. Government attitudes to mining transformed from the beginnings of modernization. For this reason, the survey considers the Qing Veritable Records only to 1850. The focus is on specific, identifiable sites that are recorded with the name of the mine or a concrete nearby location, such as a village or a mountain.

The search yielded 105 entries for the Ming period, dating between 1368 and 1623, i.e covering a span of 255 years. For the Qing, the number is 95 entries, dating between 1733 and 1844, i.e. 111 years. Some entries are mere mentions, e.g. listing a mine name among locations where a military post was maintained. Other entries are of a general, administrative nature, such as changes in government responsibilities. Many entries on identified mines are short, consisting of only one or two sentences that record the opening or closure of a mine, tax matters, or the appointment of an official. Others summarise events and more specific conditions, such as illicit exploitation, riots, taxation issues, increasing or decreasing outputs, shortfalls in tax revenues, and other matters.

The graphs and tables below show some distributions, namely

(1) The entries on the surveyed metals for the Ming and Qing and

(2) for periods of 50 years;

(3) the number of mines identified by name

(4) the geographic distribution by province and the metropolitan area for the Ming and Qing.

(5) the distribution of frequent and clearly classifiable topics for the Ming and Qing; and

(6) records on the opening and closure of mines.

Background

Interpreting the distributions requires some background regarding the source and government priorities from the late fourteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries.

The Veritable Records are the summary of all matters brought before the emperor recorded for on each day that he held his audience (in person or proxy). Diligent emperors took notice of hundreds of reported issues per day, yet the matters evidently had to be selective. Criteria for selection were either matters that required imperial decision, such as amendments to statutes and regulations or the prosecution of officials for treason or corruption, or that were considered of central relevance. The latter category comprised issues concerning defense, strategic matters, unrest and rebellion, and matters in the vicinity of the capital. Based on the overall considerations, there is reason to expect that mining matters were brought before the emperor when relevant to defense, to minting, to the court and its immediate surroundings, in the context of administrative changes, and when causing problems for social stability, severe shortfalls in revenue, or cases of malfeasance among officials.

In the broadest outlines of policies concerning the mining sector, the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty had set the tone with two statements that condemned silver mining as “evil” and accused officials who proposed using mining taxes as a source of revenue of being similar to robbers.1 Despite the highly negative representation that presumably established a great reluctance among official to broach the topic, silver mining became a source of direct revenue for the Ming court, with court eunuchs dispatched as mine supervisors. The closure of old silver mines in Fujian, Zhejiang, which had been highly productive during the Song and Yuan periods, led to illicit exploitation during the first half of the fifteenth century. Problems surrounding dwindling outputs while tax quotas remained unchanged continued and also affected Henan and Hunan. In the late sixteenth century, the Wanli emperor (r. 1572 – 1620) greatly expanded the system of eunuch mine supervisors, causing intense discontent among regular officials and considerable hardship for silver miners and local populations.2

Following the Ming tenets and late Ming literati criticism of the Wanli emperor, the early Qing imposed strict restrictions on mining. A gradual change began from the 1680s in the far southwest. Following the end of the rebellion led by Wu Sangui, the Ming general who had opened Beijing to the Manchu in order to save it from the peasant rebels and set up an initially tolerated semi-independent regional power in the southwest, the needs of supporting the army led to the rediscovery of mining taxes as an important source of revenue. Sweeping change came in the late 1730s, when the Qianlong emperor responded to Japanese restrictions to copper exports by switching the copper supply of the metropolitan mints from Japanese imports to copper mined in Yunnan province. By advance purchases of the outputs of copper, zinc, lead and tin at fixed government rates, the Qing state established a mint metal procurement system that effectively controlled copper mining in Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou, zinc mining in Guizhou, tin mining in Guangdong, and lead, zinc and copper mining in Hunan. Registration and taxation also existed for other regions and metals, but the government focus was mainly on monetary metals.3

Based on the outline of central policies, general expectations for the Ming and the Qing periods can be formulated. For the Ming, we would expect that mining was rarely brought up in the reports to the emperor, with silver mining most prominent as a direct source of court income. For the Qing, we expect great reluctance under the early emperors or roughly to the end of the Kangxi reign (1661 – 1722) and a significant interest in monetary metals, especially in copper from the late 1730s onwards.

In terms of the actual exploitation, iron evidently was the most widespread activity, with major centres in southern Shanxi and in the Foshan area, but also in Hubei and Sichuan, as well as in most areas of the empire. We may safely expect that the iron mining industry was the largest in terms of its labour force. Tax revenues, however, may not have been important. From the point of view of the number of people involved in the exploitation of other metals, silver may have been the most important sector during the Ming period, probably replaced by copper during the High Qing. The most important silver mining regions that were intensively exploited since the Song period were the highlands of Zhejiang and Fujian, with further mining areas that exploited silver, lead, copper, and later also zinc in central Jiangxi, southern Hunan, and northern Guangdong. From the Yuan period onwards, Yunnan became the most productive region of silver mining. The southwest, specifically Yunnan and western Sichuan also possess an ancient tradition of copper exploitation. Some silver, lead and copper were also worked in Guizhou and Guangxi. With the development of zinc mining, probably in the course of the sixteenth century, Guizhou rose in importance as a zinc mining region. Tin mines existed in northern Guangdong, Guangxi and at Gejiu in southern Yunnan.

Based on the geography of mining, for the five metals surveyed here, we may expect records on iron from all part of the empire, on silver mainly from Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan and Yunnan, with Yunnan certainly the region with the largest mines, on silver from Yunnan and western Sichuan, as well as Hunan, and lead from the old silver mining regions, and on zinc from Guizhou.

Discussion

Metals

The findings on the overall frequency and the distribution of the surveyed metals in part fulfill expectations. First of all, the overall frequency of entries is low, with 105 entries over 255 years for the Ming, and 95 for 111 years for the Qing. The entries cumulated per duodecade (Graph 1), however, shows a highly uneven distribution. The overall frequency is highest during the first half of the fifteenth century, falls off sharply to near nothing by the mid-sixteenth century, drops to nil from the mid-seventeenth to the early eighteenth century, to rise again in the second half of the eighteenth century to fall again to relatively low levels by the end of the century. The early Ming peak is unexpected, as it does not coincide with a corresponding hike in known outputs and suggests a break with the ideological pronouncements of the Ming founder. The very low levels through the remainder of the dynasty is more suggestive of avoidance than of low activity. The silence on the topic during the early and into the High Qing is consistent with the official policy and coincides with the lack of control over the southwest. The increase in frequency from the late 1730s coincides with the change in metal procurement for the mints, yet is not as intensive as might be expected.

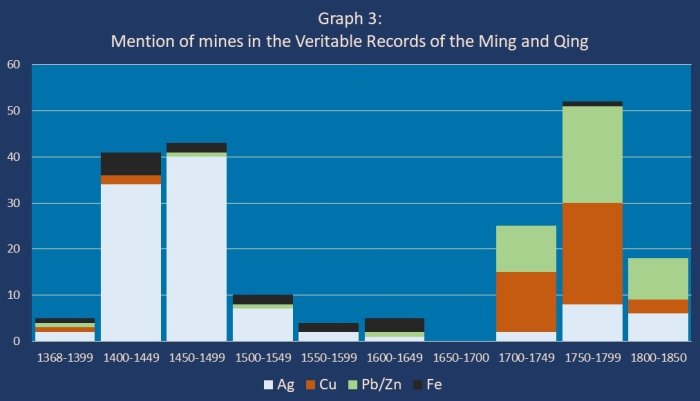

The distribution of the entries on the surveyed metals for the Ming and Qing (Graphs 2a and 2b) and the number of entries per five decades (Graph 3) present a similar mixture of expected and unexpected results. The Ming Veritable Records record almost exclusively matters concerning silver mines. It may be added that although iron mines appear to play some role, out of the total of 14 entries, 6 report on three to four small mines minor iron mines in connection with supplying the northern borders, while 4 deal small sites in Zunhua not far from Beijing. The reason for the Imperial attention was thus not mining, but military supplies and proximity to the capital. Adjusted for this coincidence creating a seeming emphasis on iron, silver is even more dominant for the Ming period. In the Qing, the emphasis on copper and zinc/lead is expected, while silver still receives some attention. The low incidence of records on iron during the Ming and the near-absence in the Qing shows that iron mining was not a concern of the central government. It apparently was irrelevant in terms of revenue while causing no problems. In fact, not a single entry is concerned with any problems caused by iron mining. We find the Ming government preoccupied with silver in part in connection with revenues and in part because of illicit exploitation and social unrest. The Qing mainly adjusted the administration of copper, zinc and lead mines for the procurement of mint metals, while also remaining interested in silver mining.

Geographic distribution

The geographic distribution (Maps 1 and 2) underlines the strong bias for certain topics and regions. Ming entries show a preponderance for the silver (and lead) mining centres in the mountain zone of eastern China, specifically in Zhejiang and Fujian, with some attention to the southwest, mainly to Yunnan and western Sichuan. The absence of any entry on northwestern China or on iron mines in central or southern China reinforce the impression that iron mining was not a topic that required imperial attention. In the Qing period, the focus of attention shifted to the southwest, specifically to Yunnan, Guizhou and western Sichuan, with occasional matters concerning south China. The relative prominence of Xinjiang with 6 entries requires explanation. It results from issues concerning people who had been banished there and were put to work in lead or zinc mines and hence is an effect of the judiciary structures rather than of mining matters. As in the Ming, iron mining remains entirely overlooked from the central perspective.

Topics

A rough classification of the types of matters (Table 1) brought before the emperor shows a wide selection of issues.

| Table 1: Overview of topics in the 186 surveyed entries in the Ming and Qing Veritable Records | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening | Closure | Increase of output | Decrease of Output | Arrears in tax/ |

Tax problems | Riots, unrest, banditry | Malfea |

Appoint |

Monetary policy | Other | |

| Ming | 4 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 6 | 14 | 18 | 5 | 35 | 0 | 28 |

| Qing | 8 | 27 | 5 | 18 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 21 | 25 | 23 |

|

Notes

Opening and closures: Entries on the formal opening or closure of a mine.

Entries reporting increasing or decreasing outputs of specific mines or mining regions

Tax arrears or arrears in fulfilling output quotas: Taxation employed annual quotas. From the High Qing, a system of advance buying of the outputs of Yunnan copper and Guizhou silver mines was implemented, which also used fixed quotas. When mines could not deliver their production quota, the advance payments became debts. Both types of arrears occasionally appear in the reports.

Tax problems: This category often overlaps with tax arrears, but also covers proposals to ameliorate conditions and reports on other problems caused by taxation

Riots, unrest and banditry: Any breaks of law and order by commoners in mining communities.

Malfeasance by officials: Reports on extortionate measures to extract revenue and on cases of corruption among officials

Administrative matters: Adjustments in administrative structures and responsibilities, official appointments.

Monetary matters: Mining matters in directly linked with the monetary policy of the High Qing, such as decisions of making mines supply certain mints, adjustments in the advance buying system for copper and zinc in Yunnan and Guizhou, adjustments of output quotas, and the handling of arrears and debts.

Other: All not readily classifiable entries from mentions of mines in other contexts, to a bandit attack on a mine, proposals to grant a title to the deity of a mine temple, to an order to guard ore left untreated after the closure of a mine.

|

|||||||||||

All entries are reports on specific matters, that are often but not always followed by an imperial decision that confirms or rejects a proposed measure. The Veritable Records contain no general programmatic statements, but imperial pronouncement had the force of law. Nevertheless, a pattern of precedents that once established were followed for all similar matters is not evident. Instead, it appears that some minor issues were brought on again, while other matters that evidently involved the central government were not brought out in audiences.

Divergences and peculiarities in the distributions of topics for the Ming and Qing periods become more intelligible with some additional information. The far higher frequency of recordings of closures of mines and decreasing productivity over openings and increasing outputs appears to reflect the general preference of representing the dispensable nature of the industry and magnanimous imperial disdain for revenues, as professed by the Ming founder. The case of the opening and closures of mines, which demonstrates interesting preferences and contingencies, is analysed in more detail below.

Shortfalls in taxes and production quotas, as well as tax problems in general are a relatively regular topic. During the Ming these concern silver mines with two exceptions, and date to the fifteenth century. During the Qing, almost all entries are concerned with arrears in output quotas of copper and zinc mines. Mining issues linked to the procurement of metals for the imperial mints for evident reasons apply only from the late 1730s and often overlap with issues of production quotas.

Illicit exploitation treated as banditry is a fifteenth-century phenomenon only, reported after the formal closure of many mines in Zhejiang and Fujian. Other cases of riots and other unlawful behaviour is rare in both Ming and Qing records.

Official malfeasance occurs only rarely. Of the 5 entries in the Ming, three are an exchange of accusations between eunuchs and regular officials for under-reporting actual revenues and for extracting taxes irrespective of mining productivity. It may be added that only 4 entries mention eunuch tax collectors, dating between 1445 and 1518. In Qing records, no entries denounce malfeasance that caused suffering among the local population. Three of the five entries deal with abusive practices in the handling of debts and arrears, while two concern the case of a treasurer of Guizhou province who was prosecuted for selling state copper on his own account.

The range of topics suggests that the imperial government addressed specific, at times minor issues as they reached the inner circle and were selected for presentation. As the criteria for selection are unclear, interpretation is conjecture. The overall frequency in conjunction with the topics shows that the Ming central government worked on solving problems in the mining administration, especially concerning the silver mines in eastern China during the early to mid-fifteenth century. Through the remainder of the dynasty, attention was rare and fleeting. During the long Wanli reign, the eunuch tax collectors find no mention in the surveyed entries.

Qing attention is more evenly spread, once the topic appeared, almost eight decade into the dynasty’s reign. The overall trend is somewhat parallel in that overall attention wanes from the late eighteenth century onwards.

Openings and closures

Entries on the opening and closure permit pursuing some of the central questions concerning the representation of mines and the processes in the central government’s administration.

The tool for pursuing the questions is provided by the fact that the proposals for opening or closing a mine in most cases record its name. This permits the targeted search for further entries on the specific site, resulting in a small series of entries in some cases and the confirmation of a singular mention in others.

The sub-search is based on the 55 entries on openings and closures.4 Ming records contain 8, Qing records 40 names of mines or places on the village-level. All eight names in the Ming records appear in more than one entry, while 19 of the Qing names appear only once. Among the latter, 5 single mentions record opening, 14 the closure only. For Pingshan 屏山 in Fujian and Mileshan 密勒山 in Sichuan, Ming records contain several entries with information on the development of the mines. In the Qing records, this is the case for Daxing 大興 and Maolong 茂隆, both in Yunnan.5 Graph 4 shows the distribution over time, together with the geographic region and a classification for importance.6

The obvious finding is the small number of records and the fact that closures by far outnumber openings. Opening and closing mines was a routine matter, which was brought out in court audiences on rare occasions for unknown reasons. We know from one of the surveyed documents, that the Ming government operated 41 silver mines in Chuzhou 處州 prefecture in Zhejiang,7 one of the leading silver mining regions of the empire. The total number of silver mines certainly exceeded one-hundred, to which mines for other metals have to be added.

Some important silver mines occur in Ming records, yet the emphasis clearly does not coincide with the silver mining region in Zhejiang and Fujian that overall received most attention. In Qing records, the overall incidence is higher, while the importance of the sites is appears very low. Only nine sites (Dingtoushan 丁頭山, Beizhe 卑浙, Kuaizhe 塊澤, Feige 淝革, Lixi 黎溪, Huangnipo 黃泥坡, Daxing 大興, Tongda 銅大, Maolong 茂隆, Hongpo 紅坡) are known from other records, of which Lixi and Maolong were major sites, while Beizhe, Kuaizhe, Daxing, Tongda, and Hongpo may have been worked on some scale.8

Adding data from other entries on the sites, the duration of operations can be established for two important Ming silver mines (Pingshan and Mileshan) and eight minor copper, zinc-lead and silver mines of the Qing period.9 In fact, with the exception of the Milesuo copper mine, which operated for 29 years, all traceable sites in the Qing Veritable Records were worked for only a few years or never proceeded beyond trial mining. The mines opened or closed in a court audience clearly were not selected for importance.

It appears therefore, that such routine matters were brought before the emperor largely by coincidence. It seems possible that they were included from time to time to provide news from the regions, following questions by the emperor or for considerations of provincial governors or even because of internal personal conflicts or needs.

The issue of the preponderance of entries on closures is slightly modified by the search for further entries. Table 2 shows the distribution:

| Table 2: Entries on mine openings and closures and information in further entries on the mines recorded by name | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Total | Single mention | Opening only | Closure only | Opening & Closure | |

| Ming | Entries | 10 | --- | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Mines recorded by name | 8 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 2 | |

| Qing | Entries | 34 | --- | 8 | 19 | 9 |

| Mines recorded by name | 40 | 20 | 7 | 24 | 10 | |

|

Notes

The divergence between entries and mines recorded by name results from the mention of several mines in some entries and the omission of specific names in others.

Single mention is not applicable for entries on several unspecified mines in an area and therefore has been omitted for entries.

The discrepancy of 20 Qing single mentions of named sites against 24 for which only the closure and 7 for which only the opening is recorded results from the fact that 11 mines are mentioned in other entries in the context of other matters, without a mention of their opening.

|

||||||

Pursuing the mines recorded by name underlines the tendency of recording closures in the Veritable Records of both dynasties. Ming records contain two entries on opening mines in administrative areas, but none on openings that also identify the mine by name. For the two identified mines with an entry on their opening, the closure is also recorded. I thus appears that the court tended to pursue matters concerning mines that had been brought to its attention as newly opened. In the Qing records, we find less consistency. The cluster of sites that were opened and reported to have been closed again some three to six years later, however, also shows a tendency to keep track of matter once brought up.

The additional records provide no explanation on the question why closures greatly outweigh openings. We have to conclude that presenting a proposal for the closure of a mine was regarded as a safe matter, more probable to be treated as good news and hence to receive the emperor’s gracious consent.

Conclusion

Overall, the survey demonstrates that:

• The Ming and Qing Veritable Records present a small selection of mining matters

• No weighting by importance could be established

• No selection criterial could be established

• The only clear but also contingent tendency is that a mine brought to the attention to the emperor could be pursued through further entries

Hence:

• The mention of a mine in this source cannot be used as an indication of its importance

• The fact that a mine is unrecorded similarly cannot be treated as evidence of its relative unimportance

• Despite higher overall frequency of entries on mining, the Qing records, the incidence of information that contributes to our understanding of mining or of the central mining administration is very limited.

References

1 In 1368, the Hongwu Emperor (r. -1368-1398), reacted to the suggestion of one of his ministers for re-opening of silver mines in Shandong: "銀場之弊,我深知之。利於官者少,而損於民者多。况今凋瘵之餘,豈可以此重勞民力。昔人有拔茶種桑,民獲其利者,汝豈不知?" (I know full well about the troubles of silver mining: They bring little profit to officials, yet great harm to the people. At present, with the recovery from suffering only just beginning, how can you even think of adding to the people’s burden? Men of the past developed tea plantations and planted mulberries so that the people would reap benefits; have been ignorant of this?!) Ming shilu, Hongwu 洪武 1 (1368)/3/14.

2 The main study on Ming mining is Tang Lizong 2012.

3 Two comprehensive studies on Qing mining for monetary metals are Vogel 1989 and Ma Qi 2012.

4In Ming records we find both „mine opening “ (kai chang 開場) and „setting up an office“ (zhi ju 置局, she ju 設局), Qing records consistently records “mine opening” (kai chang 開厰). Both ming and Qing records use the term “sealed and closed” (fengbi 封閉), in Ming records I also included entries on the abolishment of an office (ge ju 革局, ba ju 罷局).

5 Pingshan: 4 entries between 1386 and 1442; Mileshan: 7 entries between 1431 and 1489; Daxing: 3 entries between 1759 and 1770, Maolong: 6 entries, with the exception of the entry on the closure in 1801 on Wu Shangxian 吳尚賢, 1750-1768.

6 The classification for importance is generally based on external information, namely the fact that Panshan 判山, Wocun 窩村, Guangyun 廣運, and Baoquan 寶泉, were longstanding sites. Mileshan 密勒山 and Maolong 茂隆 are reported as important in the Veritable Records and in other sources. Pingshan 屏山 is not otherwise recorded but fulfilled a high tax quota and was operated for 56 year according to several entries in the Ming shilu. For Wocun, see Hecun in Dali, for Baoquan, see Liangwangshan in Xiangyun, for Mileshan, see Dayinchang in Huidong, for Maolong, see Maolong in Cangyuan in this site.

7 Ming shilu, Chenghua9/9/17 (1473): “浙江處州府松陽等縣原有銀塲四十一處”

8 Dingtoushan 丁頭山 (zinc, Guizhou), Beizhe卑浙 (zinc, Yunnan), Kuaizhe 塊澤 (zinc, Yunnan), Feige淝革 (silver, Yunnan), Lixi 黎溪 (cupronickel, Sichuan), Huangnipo 黃泥坡 (silver, Yunnan), Daxing 大興 (copper, Yunnan), Tongda 銅大 (copper, Sichuan), Maolong 茂隆 (silver, Yunnan/Myanmar), Hongpo 紅坡 (silver Yunnan).

9 Pingshan 屏山 in Fujian: 56 years, Mileshan 密勒山 in Sichuan: ca. 60 years, Luomudi 猓木底 in Guizhou 6, Ma'anshan 馬鞍山 and Jinjingou 金金溝 in Shanxi: 3 years, Meizi'ao 梅子凹 in Sichuan: 6 years, Miesiluo 篾絲羅 in Sichuan: 29 years, a mine in the Cichog 茨沖 area in Guizhou: 5 years, Huangnipo 黃泥坡 in Yunnan: 5 years, Xinglongwan 興隆灣 in Shaanxi: 3 years, trial mining only.