Terms and types of findings

This page provides definitions and discussions of the main types of findings that we collect in our fieldwork

Sites, mining areas or 矿点

Oral histories and personal experience 口述历史

Family histories 口述家史和家谱

The mines 采矿遗址

The smelting sites 冶炼遗址

Temples and stele inscriptions 庙宇和碑刻

Graves 坟山和墓碑

The sites: mines, mining areas and 矿点

The term mining site typically refers to a historic name of a mining area or the village that inherited this name. It consists of one or several mining and smelting areas, and can include one or several areas of historic settlements, temples and other structures. Strictly speaking, the sites we talk about are relatively loosely defined areas of historic mining and smelting. Because “mining and/or smelting area” is rather cumbersome, we use mines (the plural form) or 矿点 as shorthand terms.

Please note that there may be an overlap between the names of present-day villages and historic mining sites, when existing villages inherited names of historic mines. We try to avoid confusion by generally using village names for the settled area of a village rather than for the area of administrative villages and the area defined by remains of historic mining for the mining site.

The definition of a site and the area that it covers is in part a matter of interpretation. We employ the following rules of thumb:

We use historic mine names referring to the mining areas as we reconstructed them with all possible care. We integrate historic branch mines with the main mine as long as they are located within a radius of about 5 km, but define them as separate mines under the name of the branch mine when located at considerable distance (e.g. on a different mountain). In the case of several historic names referring to the same site or to sites in close vicinity, we use the earliest recorded name and record subsequent names as alternatives. In the case of a site with no known historic name, we use the name of the closest present-day village to identify the site and mark it as a stand-in by [square brackets].

Oral histories and personal experience 口述历史

Oral history comprises all information about the past that local informants relate to us in their explanations and stories as well as in practices, sites, and artefacts that they show to us. There is no doubt that oral history is the central part of our fieldwork and that we would find out precious little if we had to do without.

This thankfully has not happened so far, but we have visited sites wher e the present-day inhabitants have arrived after the end of mining and no traditions relating to the mines exist (Qianchang in Chuxiong, Ban Thi and Duc Van in northern Vietnam, Duogu in Midu). Even though observant local informants help us to find the sites still in existence, short of actually carrying out some archaeological research, we have no means of dating, identifying or further assessing these sites.

e the present-day inhabitants have arrived after the end of mining and no traditions relating to the mines exist (Qianchang in Chuxiong, Ban Thi and Duc Van in northern Vietnam, Duogu in Midu). Even though observant local informants help us to find the sites still in existence, short of actually carrying out some archaeological research, we have no means of dating, identifying or further assessing these sites.

We therefore greatly appreciate all information that local informants, whom we usually have to contact out of the blue, are able and willing to provide. We have been to sites where we picked a bad time, the busiest harvesting period, a holiday, or simply the afternoon siesta on a hot day, yet we have always found people who kindly helped us along a quest that must appear rather peculiar to many.

During our visits in villages, we try to cover the following topics:

- Sites of mining, smelting, temples, and graves; stele inscriptions of any kind, objects of any kind found or preserved that have a connection with mining;

- place names

- practical experience with mining or with the re-exploitation of historic slag and gangue, including childhood or prospecting explorations of historic workings;

- the history of the village, specifically the number of family names and the arrival of the first families;

- family histories and oral or written genealogies

- oral traditions, stories and legends relating to historic mining or village history

(1), (2) and (3) evidently is the information we need to find remains, to attach names to them, and to learn as much as possible about them. (4) helps to reconstruct the history of in-migration in connection with mining or of re-settlement after the end of mining. Because Han and Hui Chinese keep count of the generations in the male line of ancestry, the information on how many generations ago the first families settled on the site often provides a means of dating this event. (5) can provide further specific information that moreover is datable in terms of generations. (6) may not appear relevant to research in the history of technology. Stories about magical animals that leave libs transformed into ore, moving mountains that eventually are nailed into place, or the Guanyin Boddhisatva intervening to save miners before a mine collapsed evidently contain no information on technologies. Their existence, variations in widespread stories, and stories unique to a site, however, are sources on local and mobile traditions, on mentalities and occasionally even on shifts in practices and worldviews.

Orally transmitted family histories and their surviving or reconstructed written counterparts of jiapu 家谱 (family genealogies) are a mixed oral-written source that merits special mention. Although a longstanding Chinese tradition, the keeping of jiapu or other written accounts of family histories was uncommon in the late imperial Southwest. We have found a handful of genealogies of Han families, one of a Zhuang family and one of an Yi family.

Sites of mining can be mines more or less as we expect them, but not infrequently they don’t.

Past miners might have employed surface mining that left no trace or only shallow pits (鸡窝坑) and ditches (槽) that leave no or indistinct traces. There are also flushed out gullies on mountain slopes. This technology is vaguely referred to in some sources (槽、冲沟), but we doubted its existence until we found traces at tree sites. For the purpose, a water reservoir was dammed up near the top of the slope and the water released to flush down loose material (Xiyi in Gengma, Yinchangqing in Weishan, Laochang in Huize). The technology may have been used for prospecting and for harvesting native metals.

Underground mining can be differentiated into three basic technologies. We have found a few shaft mines that appear in clusters and probably are single shafts widening in the ore zone and possibly connected to a network of workings (Ngan Son in Vietnam, Huangkuangchang in Midu, Baixiang in Binchuan). We believe that these clusters represent a relatively ancient technology developed directly from pits and probably working down from the oxidized “iron hood.” Organizational structures would have involved individual claims for each pit or shaft.

Closely related are single galleries driven into the slope either horizontally of at an angle present. At some sites, numerous workings are found in close vicinity, usually clearly entering the same ore seam. Workings typically are single small tunnels of limited depth, although interconnections between the workings inside the mountain are possible. We assume organizational structures similar to the single shaft mines and that depth was defined by the end of the seam or the point where air circulation becomes insufficient at and oxygen deficiency forced miners to abandon the mine. Mines of this type typically occur in massive deposits. For this very reason, we have not encountered them too frequently – recent open pit mining of these deposits often has erased all traces of historic mines. At the same time, however, small-scale mining has employed this technology into the 21st century. Differentiating between historic, recent, and historic and recently re-explo ited mines is not always easy.

ited mines is not always easy.

Mines as we expect them from early modern to modern experience are at least partly planned systems. They typically have a main entrance that may enter the mountain at some distance from the actual ore seams and lead to an underground network of workings, ventilation shafts, and drainage galleries. Numerous mine gates or the connection of several systems are possible. We know precious little on the planning and layout of preindustrial Chinese mines, but we do know that mines of this type existed, certainly at all major silver and copper mines. While the systems of galleries, shafts and adits have evolved in the course of exploitations, certain amounts of planning are evident in drainage galleries and in straight main galleries that cut through gangue rock.

As a rule, we don’t enter mines for security reasons (workings of unknown age may not be safe under all circumstances, and even less following recent re-exploitation and in an earthquake region). We make exceptions, such as when a local guide takes us into recent mines that cut through historic workings. The majority of historic mines is no longer accessible anyhow, due to recent mining or trial exploitations. We therefore largely rely on local informants and where possible on mineral surveys. In addition, where still on site, gangue dumps outside a mine are a useful indication of the volume of material extracted.

Further indirect evidence are gangue dumps in general. In the typical setting, we find large gangue rocks at the mine mouth and fine rock chips or even ground rock where ore was prepared for smelting. Both materials are easily recognized. Thick layers of gangue are evidence of extensive underground mines, even where these can longer be found.

What we would like to find at a site of historical smelting are r emains of ore dressing, such a finely chipped gangue, of ore washing, such as water reservoirs or ditches, remains of roasting stacks and furnaces, and of course a slag dump. Such a largely complete setting is a rarity that we have so far encountered only at Fulong (with the exception of roasting structures, however).

emains of ore dressing, such a finely chipped gangue, of ore washing, such as water reservoirs or ditches, remains of roasting stacks and furnaces, and of course a slag dump. Such a largely complete setting is a rarity that we have so far encountered only at Fulong (with the exception of roasting structures, however).

The typical smelting site is a slag dump, that with some luck contains bits of furnace walls and – depending on technologies – of crucibles, retorts, ceramic rods and pipes.

Thick layers of slag free from soil are good indicators of intensive mining, while smaller smelters with some luck leave relatively intact layers of gangue with recognizeable furnace remains. Remains of intensive mining may consist of alternating layers of slags, gangue and even of debris of everyday life, indicating shifts in the use of the area over time or erosion processes. Moreover, pottery sherds may be used for dating a site by period, and charcoal or other biogenic remains can be used for C14 analysis. Unfortunately, as results of radiocarbon analysis are relatively unspecific for the period 1650-1950, the method becomes meaningful only for the period before 1650.

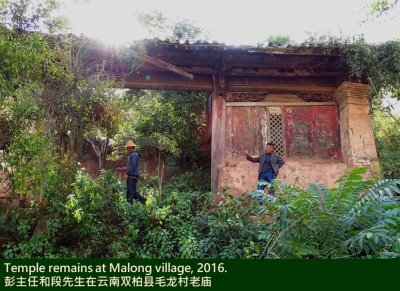

Temples and stele inscriptions 庙宇和碑刻

Temples and other remains of ritual and communal sites are extremely valuable. For obvious reasons, most surviving or still known structures date to the 19th and some to the 18th century, with some rare older stone remains. Even in the absence of any surviving remains, a known temple site is an important indication of a centre of the mining community, often occupying a position of control.

With very few exceptions, surviving stele inscriptions are related to temple construction projects. Stele that record donations by individuals or groups provide our most valuable direct records on the people and communities involved in historic mining.

Temple names often indicate the period, as deities and communal organization changed. The situation in the Ming period is largely uncertain. In the Qing, we typically find a temple or shrine dedicated to the god of ores 硔王庙, and a temple of the God of Wealth 财神庙 at productive mines. Besides, Xiyue Temples 西岳庙 dedicated to the Western Peak and the Heavenly King of Metals 金天王 played an important role. In-migrant communities were organised by province of origin, and built temples dedicated to deities that clearly identify the province. Muslim Chinese and their mosques used a communal identification by religion that in a sense also followed regional origin, as most hailed from the northwestern provinces.

The guild temples maintained by the regional communities permit tracing the presence of communities, while the size of temples reflect numbers and wealth. I should add that temples related to mines are not confined to mining areas, but may be found in cities or town that served as administrative and/or commercial centres and hence as nodes for networks of trade and mobility.

Religious traditions of mining communities outside the Han and Muslim Chinese are not known and therefore cannot be traced.

The final area that is an integral part of any historic mining are graves. Due to agricultural development and erosion, graves have been erased in the majority of sites. Where they can still be found or located, we typically find a “grave mountain” 坟山, a forested slope covered in grave mounds. At some sites, separate graveyards of Han and Muslim Chinese are known, reflecting the coexistence of two communities that kept separate religious identities. The majority of graves are simple mounds without tablets, presumably of workers who died in the mines. Some graves had stone tablets and a few even elaborate stone structures. These graves are also the ones that are more likely to survive in undisturbed settings, even erosion has erased the unmarked graves.

Gravestones with inscriptions evidently are an important source of specific and personal information.

Even when no identifiable remains survive, the existence of place names that identify grave mountains are an important indication of an established mine, and their extent is an indicator of its scale.