Fieldwork on mines in the Far Southwest of the Ming and Qing Empires and the borderlands of China, Myanmar and Vietnam

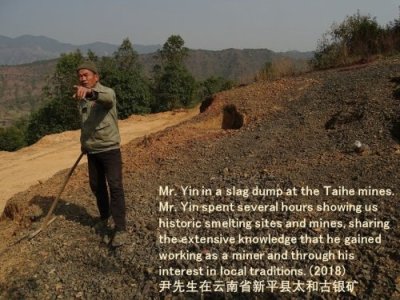

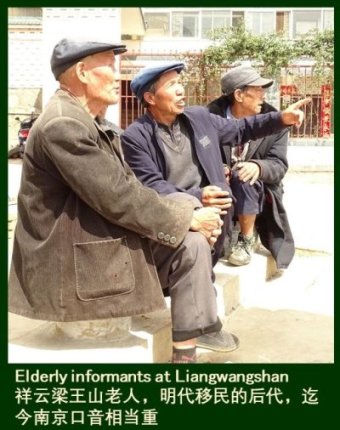

Fieldwork in this project usually consists of relatively brief visits to identified or suspected sites of historic mining, with work on site lasting between a few hours and several days. The purpose of these visits is to ascertain locations and place names, survey remains, and to collect oral histories and inscriptions. The work itself mostly consists in asking around, finding people who know about local history and, if possible, guide us to any sites.

Admittedly, this type of fieldwork is dependent on luck and even more on the goodwill of local informants. It is superficial if compared to an archaeological excavation or to anthropological fieldwork. It does, however, have the irresistible advantage of being feasible and fruitful for the purpose.

Writing these lines, I realized that you and all but the most gullible readers might correctly point out that this is a lame justification. After all, being better than infeasible or useless is not much of a recommendation.

Why fieldwork?

Research on the history of mining in China in general and in the Southwest in particular based on available traditional sources by means of modern approaches was largely complete by 1970. To grossly simplify, Quan Hansheng’s reconstruction of silver productivity on the basis of Ming and Qing tax records is a methodologically outstanding work that closed the field of research on late imperial silver mining (Quan Hansheng 1976). (>)

The slender body of materials simply did not permit research of any depth and specificity. The single body of materials that became accessible since are the Qing imperial archives, which are held in part in Taibei and in part in Beijing (the Taibei archives were made accessible earlier and therefore are named first here). Hans Ulrich Vogel and Ma Qi have made extensive use of these records, which are most detailed on copper mining in the 18th to mid-19th centuries and specific on copper earmarked to supply the Beijing mints (Vogel 1989 and his recent DFG research group, Ma Qi 2007). The field has thus seen significant new contributions. It should be noted, however, that these focus on administrative supervisory structures, as well as on the best documented period and metal.

Substantial historical research needs a substantial body of sources that can be subjected to critical analysis by close comparison and by contextualization to find out what possibly happened in the past. In the absence of such materials, doing history becomes frustrating.

This is the main reason, why doing fieldwork holds an irresistible attraction: It produces new sources!

The possibilities of fieldwork are defined by two main factors: (1) the extent of our ignorance and (2) the situation in the region today, and this is where feasibility comes in.

Factor (1) or the scarcity of written records means a considerable amount of preparatory work. The number of known sites is small, records that contain historic mine names are scattered and incomplete; we have a total of around 200 names and many have never been geolocated. A far larger number or historic mine names, in fact over 2000, is recorded in a few lists on mineral deposits of the first half of the 20th century. Again, most sites are not geolocated. Identifying the sites and relating them to present-day villages hence is the main preparatory work.

I should add that “not geolocated” refers to academic ignorance or the fact that we have no ready method of checking the actual location of the sites. People living in villages on or near the sites usually are well-aware of mining in the past. This knowledge, however, is not necessarily common outside their communities or reflected in county or other records. For this reason, visiting a site is often the only way of ascertaining the presence or absence of historic mining, the historic names, and often much more. The extent of our ignorance therefore is a main reason to cover as many sites as possible, even if this means short and cursory work on site.

Factor (2) involves the condition of traditions in remains and memories and also the possibilities of communication in terms of both inter-personal communications and travel. The fact that most of the rural Southwest was a remote backwater for most of the period from the mid-19th century to the 1990s (see the section on <a href="mm_en.html#modernity">modern history</a>) contributed to the preservation of remains and of oral traditions.

At the same time, the economic take-off and the enormous development of road and rail infrastructure that has been promoted over the last two decades greatly eased fieldwork. We can now conveniently reach most villages by car and easily communicate with informants, without encountering inhibitive differences in everyday life and outlooks. However, the building boom, urban, industrial, and infrastructure development all contribute to erasing remains and changing lifestyles. Remains disappear, while new lifestyles and new communications end the oral transmission of stories and traditions. In short, the present-day situation makes our fieldwork feasible without much effort or difficulty, but it also places us under considerable pressure to cover as much ground as we can while we still can.

I hope that the above convinced you that fieldwork is a useful means for gathering new materials for research and why we have opted for the quick and simple option. Systematic fieldwork breaks away from traditional historical research and breaks through a hitherto insurmountable barrier of substantially advancing our knowledge on late imperial mining in Southwest China and the borderlands with Vietnam and Myanmar.

The following two sections give an overview of the trips, what findings we collect and how we analyse them.

How the field trips developed

Yang Yuda initiated this departure. When we banded up for the first field trip in 2011, neither of us had great expectations with regard to useful findings. The experience at the very first sites that we visited, however, immediately convinced us that this approach was worth pursuing. However, organising a project took several years. When there was little prospect of systematic work, we decided to take a spontaneous 3-day excursion from Kunming in summer 2014, and to our surprise Li Xiaocen joined us. As a result, Xiaocen decided to pursue this line of inquiry, and prepared a joint project over several years.

Eventually, a DFG project permitted 3 years of full-time work for me, and 5 field trips. As a team of two, Yuda and myself confined ourselves to the most important silver mines. Xiaocen, however, approached the issues with more courage and envisioned a co-operation project on copper and other metal mines. This project suddenly reached a stage of concrete preparation in 2017 and was a success at first submission. This current co-funded DFG-NFSC project allows us to continue work with a wider focus for the period 2019-2021.

Fieldwork trips with my participation so far are:

- March-April 2011: Yang Yuda and Nanny Kim

- August 2014: 3-day trip Nanny Kim, Yang Yuda and Li Xiaocen

- November-December 2015: Yang Yuda and Nanny Kim, with Ma Qi, Zhang Kefeng and graduate students of the History Department of Yunnan University

- November 2016: Nanny Kim and Yang Yuda,

- October 2017: Nanny Kim, Li Xiaocen and Liu Peifeng

- November 2017: Nanny Kim, Yang Yuda and Vũ Đường Luân

- March 2018: Nanny Kim and Yang Yuda

- June 2018: brief trip Nanny Kim with Shen Kaxiang and Rebecca O’Sullivan

- March-April 2019: Nanny Kim and Liu Peifeng

- August-September 2019: Nanny Kim and Liu Peifeng, with Bu Chaoqun and Zhu Xiangyin, and Nanny Kim and Li Xiaocen

Note: names of participants in the order of the person who served as the guide of the team to the largest number of sites visited during the trip

Fieldwork findings and their analysis

As you may have gathered from the above, we basically go to sites that we have been told about or that we have located with fair probability, ask around to collect any information that local informants know about and are willing to provide, and walk about to look at any remains still existent or sites where local informants remember them to have been.

This work requires the support and time of local informants who live in the villages at or near the historic sites. At times, we are supported by village governments, members of the Culture Stations of town or village compounds, the county Cultural Relics Office or the County Museum. In addition, at sites where mining is still in operation or has been operated over some period in the past decades, support by mining companies is important. Village governments often help with finding informants; cultural institutions have already carried out fieldwork on some sites and can provide valuable records of their own as well as guidance to sites and informants; companies provide access to sites and informants with engineering background and often with rich knowledge on the historic mines. Occasionally, they also provide access to company archives.

In other words, we are mostly a nuisance and an interruption of regular work. Being aware of this, we appreciate the support and try to minimise the disruption. In our reports, we document our sources of information, although using full names only for colleagues in the cultural institutions. I may add that our presence can at times be received not only with due hospitality but with some interest, especially in interviews with senior citizens, as people enjoy sharing their memories. The return of our work for local communities may not be immediately evident. The visits themselves contribute to keeping the memory of past mining awake and may help to foster pride in local history. By using our materials, you also contribute to getting to know otherwise undocumented local histories.

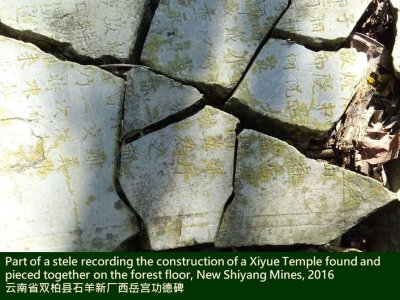

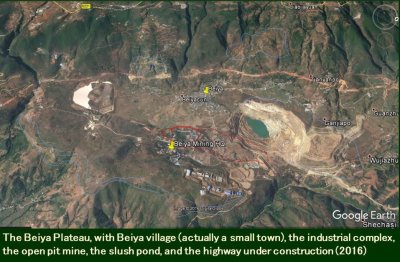

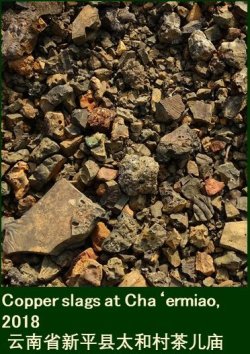

The materials we bring back include field reports, photos and - if available - specimens of slag, ore, gangue or metals. The first work step back home is ordering and geolocating the materials. Until recently, my geolocation was confined to Google Earth, with GPS data now added for important sites. First results are direct findings or new interpretations from comparing the results from the analysis of historic records and field results.

The result of this work step are the materials that you find here, consisting of (1) an analysis of historic records and other materials, (2) the field report(s), (3) simple maps for general orientation, (4) photos and (5) fieldwork results.

The definition of the sites requires a short explanation:

Each site is typically identified by a historic name of a mining area or the village that inherited this name. It consists of one or several mining and smelting areas and can include one or several areas of historic settlements, temples and other structures. Naturally, the sizes of the areas and the scale and durations of the exploitations vary greatly, ranging between Gejiu 个旧, a huge mining area that covers two mountain massifs with a total area of some 225 sqkm to sites of the size of a few fields with some smelting remains only. (To keep the numbers of sites from ballooning out of proportion, we have grouped the very small sites with associated larger sites.)

In some cases, mines in close vicinity are grouped under a single site. This applies when several sites have been identified in close vicinity with some uncertainty as to the historic names and present-day sites. In a few cases, we have also grouped separately identified but closely related sites together simply because this makes presentation and discussion more economical.

There are some cases of uncertainty. There are sites of historic mining with no known historic name. In this case, we use the name of the closest present-day village to identify the site and place it in [square brackets]. In a few other cases, identification is genuinely uncertain, with several historic names possibly referring to the same site or a single name covering several sites. We indicate uncertain identifications in the notes. When relations between a core mining area and smaller-scale exploitations could be clearly established, we list only the main mines.

If you’d like to learn more on the types of findings, how we define them and what we do with them, you can find more information here.