The Construction of Japanese Buddhist Identities in the encounter with Sri Lanka, 1871-1893

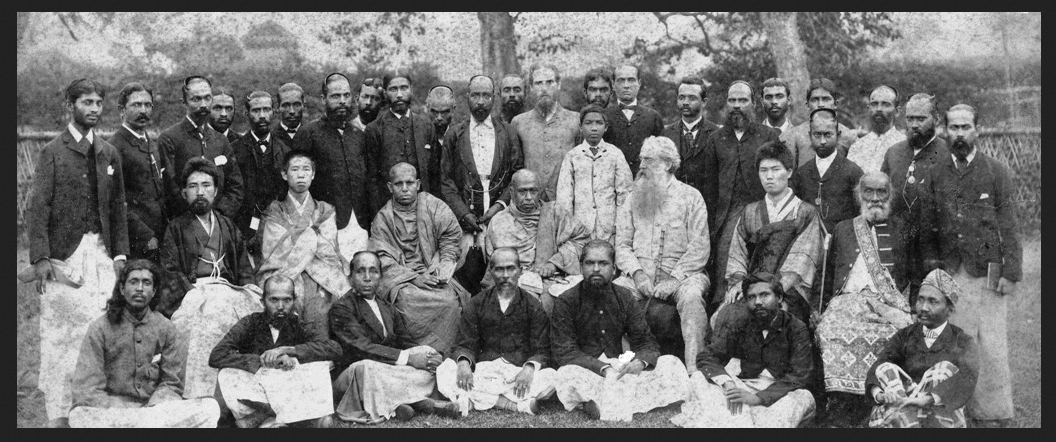

Japanese, Ceylonese, and Western Buddhists in Colombo, 1889. On the extreme left, sitting on the floor, Dharmapāla; behind him on chairs Noguchi Zenshirō 野口善四郎 and Yoshitsura Hōgen, 善連法彦; in the middle Hikkaduwe Sumangala; on the right from Sumangala H.S. Olcott, president of the Theosophical Society; on the right beside Olcott Higashi Onjō 東温譲 (1867−1893).

The Project

The World Parliament of Religions that took place in Chicago on September 11th, 1893 is rightly considered to be a turning point in the history of the modern western reception of Buddhism. For the first time, Asian Buddhist agents were offered the opportunity to present to the wider international public their own vision of the newly discovered "world religion Buddhism". Of particular importance were the contributions of the delegates of Sri-Lankan and Japanese Buddhism, as these two countries were the cradle of Buddhist modernism and hence fundamentally shaped the religion's modern history. Although the Parliaments organisers sought to promote the harmony of religions (led by Christians, of course), there arose a, if subtle, struggle behind the lecterns of the Parliament as to who could claim the right to define what a "modern Buddhism" actually was. While the Japanese delegation enthusiastically appropriated the understanding of Buddhism as a religion and endeavoured to dismiss South and Southeast Asian Buddhism as a primitive "Small Vehicle", the Sri-Lankan monk Hikkaduwe Sumangala (1827-1911), in his written salutations delivered by none other than Anagārika Dharmapāla (1864 - 1933), rejected emphatically the category of "Buddhism" as a western and Christian construct and emphasised instead the rationality, scientific nature and social achievements of the "orthodox" ārya dharma transmitted in Southeast Asia.

Hence Japanese and Sri-Lankan Buddhism both forwarded their own claims for representing Buddhist modernity, a modernity from which they sought to exclude the respective other. And yet, there was a certain consensus among the feuding traditions as to how a modern Buddhism should look in practice beyond philosophical and dogmatic sophistry. Both parties emphasised: the rational nature of their tradition as compatible with science; individualism and inwardness; support of a this-worldly asceticism and disparagement of the authority of traditional religious experts and virtuosi, as well as of the ritual technologies associated with them, or the substitution of the latter by simplified forms; texts and their standardisation in canons; and finally the establishment, often inspired by Protestantism, of new institutional forms such as lay religious associations and missionary strategies such as the use of printed media.

The Buddhist performance at the World Parliament thus reveals a complex entwinement of identity-building processes in the genesis of Buddhist modernism. In previous scholarship, these were understood with regard to the criticism of colonial and orientalist power structures as arisen from the encounter of "traditional" or "premodern" Buddhist communities in various Asian regions with the overwhelming modernity of the West. The project presented here attempts to expand this narrative by the decisive factor of the mutual encounter of Asian Buddhists, focusing on the relationships between Sri-Lankan and Japanese Buddhists before the World Parliament. These relationships began during the first explorations of Asian and Europe, which Japanese Buddhists undertook immediately after the Meiji Revolution. Already in 1871, a delegation of the Ōtani branch of the True School of Pure Land school visited Sri Lanka on their way to Europe andcame to the startling conclusion that their Sri Lankan coreligionists were devotees of the Buddha Amida. This misunderstanding contributed substantially to the dispatch of Kasahara Kenju 笠原研寿 (1852 – 1883) and Nanjō Bun'yū 南条文雄 (1849 – 1927) to Europe, where they studied Sanskrit in Oxford under Max Müller. It also marks the beginning of increasingly close contacts between the Japanese and Sri-Lankan Buddhist traditions, which reached a first climax with the arrival of the Shingon monk Shaku Kōzen 釈興然 in 1886. In the years between Kōzen's arrival and the World Parliament, eleven Japanese Buddhists came to Sri-Lanka to study, more than twice as many as went to study in Europe during the same period.

Shaku Kōzen 釈興然

This three-year project supported by the German Research Foundation aims at illuminating the networks and activities of these early Japanese travellers, how these were received in Japan, and the ways in which they contributed to the Japanese perception of Buddhism as a "world religion". As a long-term objective, the project seeks to demonstrate the active role and agency of Asian Buddhists in constructing the image of modern Buddhism and thus make a contribution to the provincialisation of Europa in the modern history of religions.

Publications

- Stephan Kigensan Licha, “The Small Vehicle: The Construction of Hinayana and Japan’s Modern Buddhism”, Monumenta nipponica 76/2, 2022.

Talks

- Staphan Kigensan Licha, “Buddhist Modernism in Sri Lanka and Japan Before 1900”, Universität Heidelberg, November 2021.

- Stephan Kigensan Licha, “The Eastern Small Vehicle – The Construction of Hīnayāna at the Crossroads of Japan, Sri Lanka, and Europe”, European Association of Japanese Studies, August 2021.