Nezha at Liangmaqiao

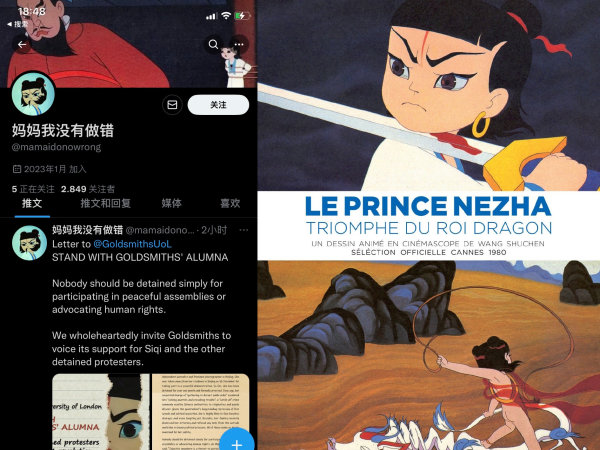

When a call of solidarity for the Goldsmiths’ alumna Li Siqi 李思琪, who was detained for taking part in a demonstration in the context of the din A4 revolution at Liangmaqiao 亮马桥 in Beijing, was published on social media on January, 28th one of the things that particular stood out was its use of the imagery from a 1979 animation movie. The movie in question is Nezha Conquers the Dragon King 哪吒闹海, one of the most famous movies of the Shanghai Animated Film Studio. Which begs the question what motivated this choice? What is behind the image of the boy with the fearsome gaze and the two hair buns that some have christened an oedipal god?

Who is Nezha?

In matter of fact, Nezha is Nalakūbara, a heavenly god in Indian Buddhism. He is the son of Vaiśravaṇa the king of the Yaksha (original sometimes malevolent nature spirits). He journeyed to China via the Buddhist translation movement. Accordingly, many elements like the returning of his bones and flesh to his father and mother respectively as well as his re-birth from a lotus flower also go back to Buddhis traditions, particularly Chan-Buddhism. In this context the first element is seen as a metaphorical allusion to the process of leaving the family to become a nun or monk. In Chan-Buddhism it is used to reflect on the question of how Nezha was able to separate his flesh from his bones. But it he didn’t remain only a part of the Buddhist canon. He developed his final form via local religious believes, thorough which also Nezha became part of the Daoist canon. As such, he still plays a role in Taiwanese folk religion as can be seen in the margins of Tsai Mingliang’s debut movie Rebels of the Neon God 青少年哪吒 (1992). The Chinese title also alludes to Nezha and not a neon god.

Investiture of the Gods

Nezha received his prevalent form in the late Ming novel Fengshen yanyi 封神演义 or Investiture of the Gods. There, his legend is placed in the context of the victorious struggle of the Zhou 周 against the failing Shang 商 with the help of multiple (future) gods and Daoist priest. In the novels telling, Nezha is the third son of Li Jing 李靖, after Jinzha 金吒 and Muzha 木吒. Following his magical birth, Nezha gets in to conflict with the Dragon King and his Yaksha or Ye Cha 夜叉 who are now marine demons. A struggle ensues in which Nezha is not only victorious, but which also sees the dragon king’s son slain. After his son got killed, the Dragon King is threatening Nezha to kill him and his family in retribution. This outcome can only be prevented by the returning of the flesh and bones to his parents, to remove any affiliation from them and also to atone for his guilt. Nezha is reborn with a lotus body with the help of his master Taiyi Zhenren 太乙真人. Upon his return he clashes with his father partially over a temple founded in his name by his mother, which his father destroys. Thanks to his superior powers Nezha is destined to win but the patricide is merely prevented by heavenly intervention when his father is given the power over a pagoda, or rather a model of one, which he can control and expand to contain his son. In the end the oedipal conflict between father and son isn’t resolved but continues in a peculiar balance.

Beyond this self-contained narrative, Nezha as well as his father and brothers are made part of the campaign of the all-important kings Wen 文 and Wu 武 of Zhou 周 against the last Shang 商 King Zhou 纣 under leadership of the Daoist Jiang Ziya 姜子牙. After its conclusion he and the rest of his male family – as well as host of other figures – are invested as gods into the heavens, hence the name of the novel.

Other versions

This popular story did have its responses in different kind of dramatic forms, particular movies. There is a movie version by the Great Wall Film Company during the early days of Chinese cinema as Nezha Chushi 哪吒出世 or Birth of Nezha as well as a 1962 Cantonese adoption under the same name during the peak of the Hong Kong studio system. Even recently there are two animated versions dealing with the Nezha material in an updated manner – according to Thomas William Whyke and Joaquin Lopez Mugica. These are Nezha: Birth of the Devil 哪吒之魔童降世 (2019) and New Gods: Nezha Reborn 新神榜:哪吒重生 (2021). But in updating the material both let go of the self-mutilation, which makes them hard to comprehend within the other versions where this act takes up such a central part. The most impactful version of which might be the one of the Shanghai Animated Film Studio 上海美术电影制片厂 of 1979.

Shanghai Animated Film Studio

Formed in 1957 it is majorly known for two works, one of them is Nezha of 1979 and the other one is Uproar in Heaven 大闹天宫 (1965). It is an animated depiction of the origin story of the Monkey King in the Journey to the West 西遊記, another Ming dynasty novel (predates Investiture of the Gods but also features a Nezha character fighting and losing to the Monkey King), that is quite famous in its own right.[1]

The Nezha version they produced over the time period of 15 months was directed by Wang Shuchen 王树忱. While it is a retelling of the relevant section of the Ming dynasty novel, it nonetheless takes some liberties in order to stress the point of a rebirth – according to the director – of traditional themes after the time of the gang of four 四人帮 (metaphorically present in the four dragons). On the other side the story itself is made more obvious political. Nezha is for example moved to his famous act by the plight of the people who are threatened by the dragon kings to be swept away by floods. This makes Nezha a hero of the people.

This is stressed further by the ending of the movie that forgoes the final battle with his father, instead he is showing to be greeted by representatives of the people, among them the children he rescued earlier. Plus, underlining the partial consistency with the political moviemaking, he is then seen riding his deer into the sunset, even if it isn’t the red sun of old. Nevertheless it still can be seen as underlining a resolution of the conflict, the restoration of the hero, and the breaking of a better future.

More recently the studio is also involved in the promotion of the Beijing Winter Olympics, depicting their famous creations – among them Monkey King and Nezha looking similar to their 60’s and 70’s depiction engaged in winter sports, speaking to the lasting fame of these rebellious figures.

Rebellious character

With an outline of the story at hand and the also some inside into its famous version, we can summarize what make Nezha a suitable symbol for Li Siqi. At its core is the act of self-mutilation an act, which works in defiance of his father and inhumane traditions and the natural order as symbolized by the dragons. With their number and keeping in mind the director’s intention for this movie to be a re-birth of tradition, the dragons are a symbol political directed towards the gang of four and against other political injustices associated with the Cultural Revolution. As such, the movie and Nezha’s selfless struggle against them can always be seen as something of a call against political injustices. Nevertheless, by going so far as even disregarding his own body along the way, the movie is not only adding to the selfless aspect of the character, but still alluding to the conventions for heroes still present at the time. Accordingly, Nezha of 1979 is still very much bound to its time. But beyond the context of the movie’s production, these changes to the character also allow for him to be much more of a rebellious character in general. Furthermore, by forgoing the final confrontation with his father, the movie sheds away the traditional order in which he was akwardly placed before, making Nezha a weirdly modern figure.

To underline this idea one can point to the violence and cruelty in his rebelliousness against – for example – the dragon king’s son when he uses his sinew to make a belt. These violent tendencies and his martial powers are also behind Nezha’s appeal as an incarnation in Taiwanese folk religion. There, the re-incarnated child god works as model or a cathartic outlet for masculine role; living out drives that are not accepted. Additionally, he is being taken up by weaker members of a male dominated society. They are using him as a symbol of resistance, as for instance mothers in how to deal with their similar rebellious children – a point that is depicted in Tsai Mingliang’s movie mentioned above.

What differentiates this part of the Nezha phenomena and the character in the 1979 movie is the political notion in sacrificing oneself for society. And crucially while the traditional Nezha is somehow placed into a greater (Daoist) order, there is basically no real limit to his powers in the movie version. This part of the version as an all-powerful youthful rebel makes him in turn a stable in another field – rock music.

Beijing Music-Scene use of Nezha

Times changed from the point when rock music got introduced in the (late) 1980’s, a time mostly associated with names like Cui Jian 崔健 or the band Tang Dynasty 唐朝乐队, all based in Beijing. Since then, one can make out multiple hot spots in the mainland. At least in the early 2000 one can consider Wuhan, Nanjing and Chengdu as being home to vibrant (rock) music scenes besides Beijing. Nevertheless, among those, Beijing still takes a special rang as the-place-to-be because of the many labels calling it their home over the time. This also makes it to a very competitive arena were many bands go under before getting noticed in the wider scene.

There are two bands in the Beijing music scene which make use of Nezha. The first one I want to mention directly uses Nezha in it is name. This band had a rather short career starting of 2004 or 2006 (depending on the source) and lasting until 2008, with this it belongs to the ones that didn’t quite make it. Their only album He is outside of the gate of time 他在时间门外 can be seen as rather eclectic mix of college rock, Japanese pop rock, and some harder rock stiles, all in all reflecting popular stiles of the time. Beyond, the name the band uses samples from the 1979 movie.

On the other more known side we have the band Miserable Faith 痛仰 which majorly uses Nezha in their imagery. Starting of as a Hardcore Band in 1999 their migrated to a more pop rock style with their album The Music Won’t Be Stopped (literarily Don’t Stop My Music) 不要停止我的音乐 in 2008. This change was also marked by a seemingly calmer Nezha on the cover. Beyond their use of Nezha to signal a change in style the band is more widely recognized for the use of a particular frame from the 1979 movie. Exactly the frame where Nezha with angry face is holding the sword to his throat about to killing himself, facing the inevitable with a grim face. At first this image was just be the band for their 2006 album No 不. Since then, the motive is used as a banner in the background of the band’s performances and can also be seen as on a flag waved by their audience. More widely it also has been adopted as a profile picture by fans of the band particular following their breakthrough after their appearance at the band contest show The Big Band 乐队的夏天. In the wake of this popularization of the band and steep rises in their ticket prices, the use of the Nezha imagery also led to some confusion around the use of Nezha; does the person use Nezha because of what he means for her or because he wants to signal allegiance to Miserable Faith? Importantly, this use of the imagery of the 1979 movie – how much confusion it may have sowed – it helped to keep it alive and spread it, in its fearlessness.

Conclusion: Nezha at Langmaqiao

In the end it is now less surprising that the campaign around Li Siqi used the 1979 Nezha to suggest the same fearlessness in facing the potential consequences. But looking at the details, the actual frame that is chosen as the background image isn’t the iconic one that is adorning the banner of Miserable Faith, rather it is the moment where the father turns away from his rebellious son who is tied to a mast, delivering him to the dragons. This peculiar choice – underlined by the name of the account name 妈妈我没有做错 and handle @mamaidonowrong; seemingly mimicking Nezha’s calls at that moment – puts the focus on the abandonment felt by Nezha and by extension Li Siqi as well as others who choose to stand there at Liangmaqiao. They are appealing to an authority figure that chooses to forsake them, and in the end, leaves them no other direction to go than to fight on by themselves, just like the heroical figure yet again working as cathartic symbol.

Joost Brokke

Sources:

Boretz, Avron Albert. “Martial Gods and Magic Swords: The Ritual Production of Manhood in Taiwanese Popular Religion.” Ph.D., CornellUniversity, 1996.

Macdonald, Sean. Animation in China. Routledge, 2015.

Shaḥar, Meʾir. Oedipal God. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2015

Whyke, Thomas William, and Joaquin Lopez Mugica. “Calling for a Hero: The Displacement of the Nezha Archetypal Image from Chinese Animated Film Nezha Naohai (1979) to New Gods: Nezha Reborn (2021).” Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 15, no. 3 (September 2022): 389–409..

Witt, Barbara. Die „Nezha-Legende“ im Roman Investitur der Götter (Fengshen yanyi): eine literaturwissenschaftliche Untersuchung und Kontextualisierung. Lun Wen – Studien zur Geistesgeschichte und Literatur in China 25. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2020.

[1] There are overlaps between those two movies. An important one is the palace of the jade emperor, while it is precisely this temple that is shaken up in the Chinese title of the Monkey King film, in Nezha the palace is found empty. A closer parallel is that in both films the overpowering main characters are not put back into the hierarchical order, different from their respective source text. This enhances the rebellious quality in both depictions.