Debates on the Nanfang Zhoumo Incident of January 2013

The Debate on China's Popular Micro-blog Site Sina Weibo

by W.E.

After many of the reporters working for Nanfang Zhoumo had declared themselves on strike by Sunday, January 6, 2013, the conflict exacerbated. By Sunday night, the protests had transformed into a real-time debate within the Chinese blogosphere, particularly on the internet platform Sina Weibo. This platform, which was established in 2009, has more than 300 million registered users and is comparable to the American platform “Twitter”. There are more than 100 million short text messages (called “weibo” 微博, literally “micro-blog”) posted per day. The topics that are discussed on Weibo range from ordinary daily activities over consumption practices to current social and political issues.

One day after the strike became public the Chinese Wikipedia article discussing the Nanfang Zhoumo incident already consisted of four sections with the first subsection concerning “The matter about the official micro-blog on Weibo” (官方微博问题) (see DACHS catalogue). The original conflict of the New Year editorial, published on January 3, had been intensified by disputes about the contents of the newspaper's official profile on the internet platform Sina Weibo. On Tuesday, the article had been further expanded to a total of six sections with the second one heading “The resistance movement on the micro-blog site Weibo” (微博上的抗争) (see DACHS catalogue), which later in the day was again modified to “The incident fermenting for a second time on Sina Weibo” (事件在新浪微博上的二次发酵) (see DACHS catalogue). These changes of the heading could be understood as representing a discourse between the different authors writing for Wikipedia. Although the particular role of each author had not been crystallized yet, the authors seemed to agree, that the debate on Sina Weibo was an integral part of the incident.

The conflict on Weibo started on Sunday evening with the announcement “To the Readers” (致读者) that was published on the official micro-blog of the Nanfang Zhoumo newspaper. The blog post stated that the New Year special edition had been edited by the reporters of the newspaper themselves and thus had not been censored by the top party propaganda official in Guangdong province, Tuo Zhen (庹震), as journalists had claimed before: “The New Year special editorial that was published on January 3, was edited by our reporters and the preface on the cover was composed by a person in charge from Nanfang Zhoumo. All rumors that have been spread on the internet concerning the editorial are false. Owing to deadline constraints and inattention on the part of our reporters there appeared to be some mistakes within the article. For this we would like to express our apologies to the readers.” (本报1月3日新年特刊所刊发的新年献词,系本报编辑配合专题'追梦'撰写,特刊封面导言系本报一负责人草拟,网上有关传言不实。 由于时间仓促,工作疏忽,文中存在差错,我们就此向广大读者致歉。) (See DACHS catalogue)

Only two minutes earlier, at 20:18, Wu Wei (吴蔚), the reporter in charge of the official Nanfang Zhoumo micro-blog posted a message on his private Weibo account saying that he had been made to give up the official micro-blog password and he was no longer responsible for the contents written on the official Nanfang Zhoumo’s account (see DACHS catalogue). This post was removed from Wu’s private microblog only shortly thereafter. At 21:23, three minutes after the official announcement had been posted, the micro-blog of the Nanfang Zhoumo’s cultural department published the following blog post: “At the moment, the official Weibo no longer belongs to Nanfang Zhoumo.” (官微目前已不屬於南方周末) (see DACHS catalogue). Later in the evening, at 22:27, the economic department engaged in the protest and posted a message that said: “The Nanfang Zhoumo’s Weibo account was taken over by force, […] the official statement ‘To the Readers’ in no way represents the actual facts […].” (南方周末新浪官方账号已被强行收缴,此微博在2013年1月6日21点30分发表的《致读者》,并非真相,我们将陆续通过公开途径发布准确信息。) (See DACHS catalogue) The debate on the former printed New Year editorial had transformed into an online debate about the credibility of the Nanfang Zhoumo newspaper in general. One can roughly spot two different parties among the journalists, one supporting the official Weibo account, and one using the accounts of separate departments and their private microblogs respectively to oppose the official position.

In the next morning, January 7, the newspaper Global Times (环球时报), which publishes under the patronage of the party organ Renmin Ribao (人民日报), reacted to the Weibo debate and published an editorial concerning the official statement: “The official micro-blog post by Nanfang Zhoumo last night made things clear. The truth and the version [of the original editorial] that circulated on the internet during the last days absolutely do not correspond to each other. […] [T]he so called ‘revision’ was clearly not written by the propaganda ministry of Guangdong province.” (昨晚南周的这条官方微博,把事情起因做了澄清,真相与前些天互联网流传的版本完全不同。[...]所谓“改稿”确实不是广东省委宣传部所写。) (See DACHS catalogue) Instead of calming the waves of protest that had emerged within the online blogosphere, this article triggered even more online reactions. Tan Mintao (谭敏涛), a lawyer from Xi’an, wrote an article on his private Sina blog “Tan Mintaos Farm of Laws” (谭敏涛的法律农场), commenting the Global Times’ editorial: “Who would have thought that the Global Times tenaciously would grab hold of the official statement posted on the Nanfang Zhoumo’s microblog after that very same account got captured and use this announcement to make a headline out of it. […] [T]his kind of media consciousness is only good for one thing, namely producing evil together with the authorities.” (未曾想到,环球时报死死抓住南周微博被收缴后的官方声明来大做文章 […] 这样的媒体良知,只会和权力共同作恶。) (See DACHS catalogue) At the end of the article, online users posted their support for the reporters on strike and linked the blog post to their individual micro-blogs on Weibo.

Online support via Sina Weibo also came from celebrities and well-known commentators. “[..] [H]oping for a spring in this harsh winter.”, Li Bingbing (李冰冰), a Chinese actress, said to her more than 19 million followers on her micro-blog account on Monday, January 7.

Yao Chen (姚晨), an actress with almost 32 million followers, posted the logo of the Nanfang Zhoumo newspaper and cited a quotation by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Russian Nobel laureate and dissident: “One word of truth outweighs the whole world”.

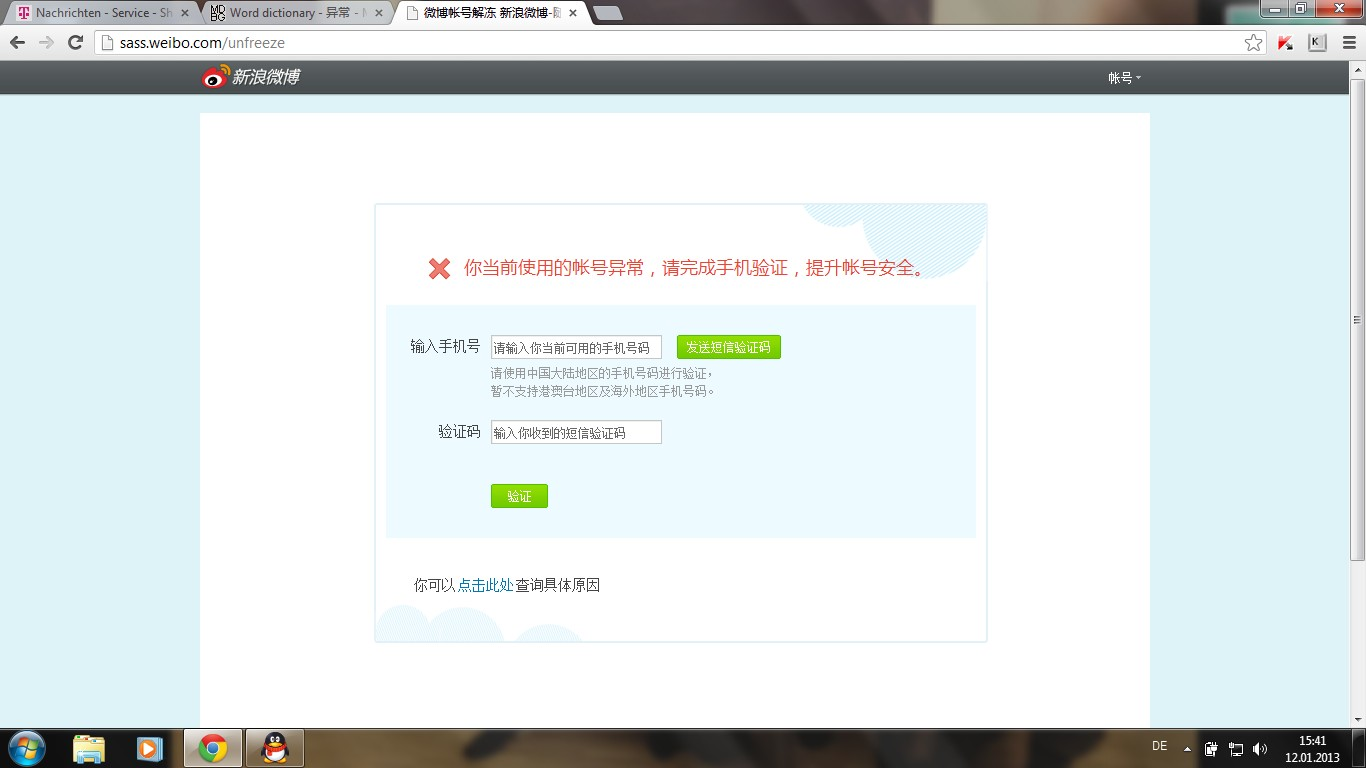

In order to bring down the wave of protest messages, the search function on Sina Weibo blocked words relating to the incident like “south”, “weekend” or “editorial” and blog posts or comments containing those words were removed from the platform. After the removal, a new message appeared in the place of the former blog post saying “Sorry, this micro-blog post was not suitable for the public. If you need any help, please contact our customer service.” (抱歉,此微博不适宜对外公开。如需帮助,请联系客服。) (See DACHS catalogue)

On Wednesday, January 9, the Chinese BBC website published an article, asking the question “The Nanfang Zhoumo incident – Will the online storm go without any injuries?” (南方周末事件 网络风暴去无痕吗?) (See DACHS catalogue) By that time the internet censorship had been extended to the blocking of whole Weibo accounts. Even celebrities from Taiwan, like the actress Yi Nengjing (伊能静), found that their accounts were no longer accessible after posting their support for the Nanfang Zhoumo’s journalists on strike or calling for more freedom of the press. (See DACHS catalogue) Nevertheless in most of the incidents it was possible to authenticate and rehabilitate the account after some time. An extremely harsh online policy, using such means as censorship and liquidation, together with strictly guided news reporting in the print media, might be one of the reasons why the so called “online storm” or “digital resistance movement” came to a nearly complete halt within the short time of only one week.

DACHS Leiden

DACHS Leiden